Scott Pilgrim vs. the Movie Adaptation

Aug. 21st, 2023 06:47 pmOver the years since its final issue in 2010, Bryan Lee O’Malley’s Scott Pilgrim comics have attained a ‘cult classic’ reputation for their playful, video game-esque tone and bombastic action scenes, largely aided by how well those elements were translated into Edgar Wright-directed 2010 movie Scott Pilgrim vs. The World. The adaptation had a hard job to do: scriptwriting started when only the first book had been published, and O’Malley purposefully did not write the series with an ending in mind (from O’Malley’s blog). This unfinished 6-book story was being cut down into a feature film runtime, and something had to go.

Unfortunately, what had to go, and ended up disappearing from most people’s idea of what Scott Pilgrim was, were the most interesting aspects of the comic (at least to me.) Because Scott Pilgrim isn’t really a story about cool fights and dream girls—well, it is, but Scott Pilgrim is a story of how cool fights and dream girls are both facades for these painfully human, complex dynamics and pasts, and beneath its bombastic action lies an unexpected and fascinating story that the movie misses, and ends up presenting a shallower and more misogynistic piece of art.

Furthermore, that ‘cult classic’ status, and the way the comic plays with expectations and metanarrative, has caused it to develop a sort of aura of reputation and tropes that makes reading and watching it this fascinating thematic soup—and baby, I have autism, so let’s get picking bits out of it.

WORLD ONE: TIME-TRAVELLING DIAMOND-CUTTER SHAPED HEARTACHE

WORLD ONE, LEVEL ONE: MAKE IT OR BREAK IT

A key part of experiencing the Scott Pilgrim comics is how they evolve over time. A comic’s job is to seamlessly match up art to writing to panelling, and over the course of the 6 volumes, all three grow in complexity. Scott Pilgrim’s early messy and simplistic art style (grounded by a solid understanding of 3D form) feels perfectly in step with its off-beat, awkward dialogue. At this point in the comics, Scott is an affable asshole mocked by all of his friends, who seems to get everything he wants—’If your life had a face, I’d punch it.’

This speed is largely upheld by the panelling. Panelling, similar to video editing, is an invisible art that holds everything together. Unless you’re a nerd, like me, you’re probably not taking active notice of how a comic is panelled when you read it, but it’s integral to how you experience it, because it frames (literally) the comic in time. The panelling in the first half of Scott Pilgrim is effortlessly pacy, and sticks to a strong structure: full bleed panels every page, taking up as much page space as possible, giving us speed and efficiency in what it shows. The ridiculous fights, crazy concepts like subspace, and Scott’s own awful behaviour are all held in place and made easy to accept by the fact the comic never stops and gives you enough time to actually think about what’s happening.

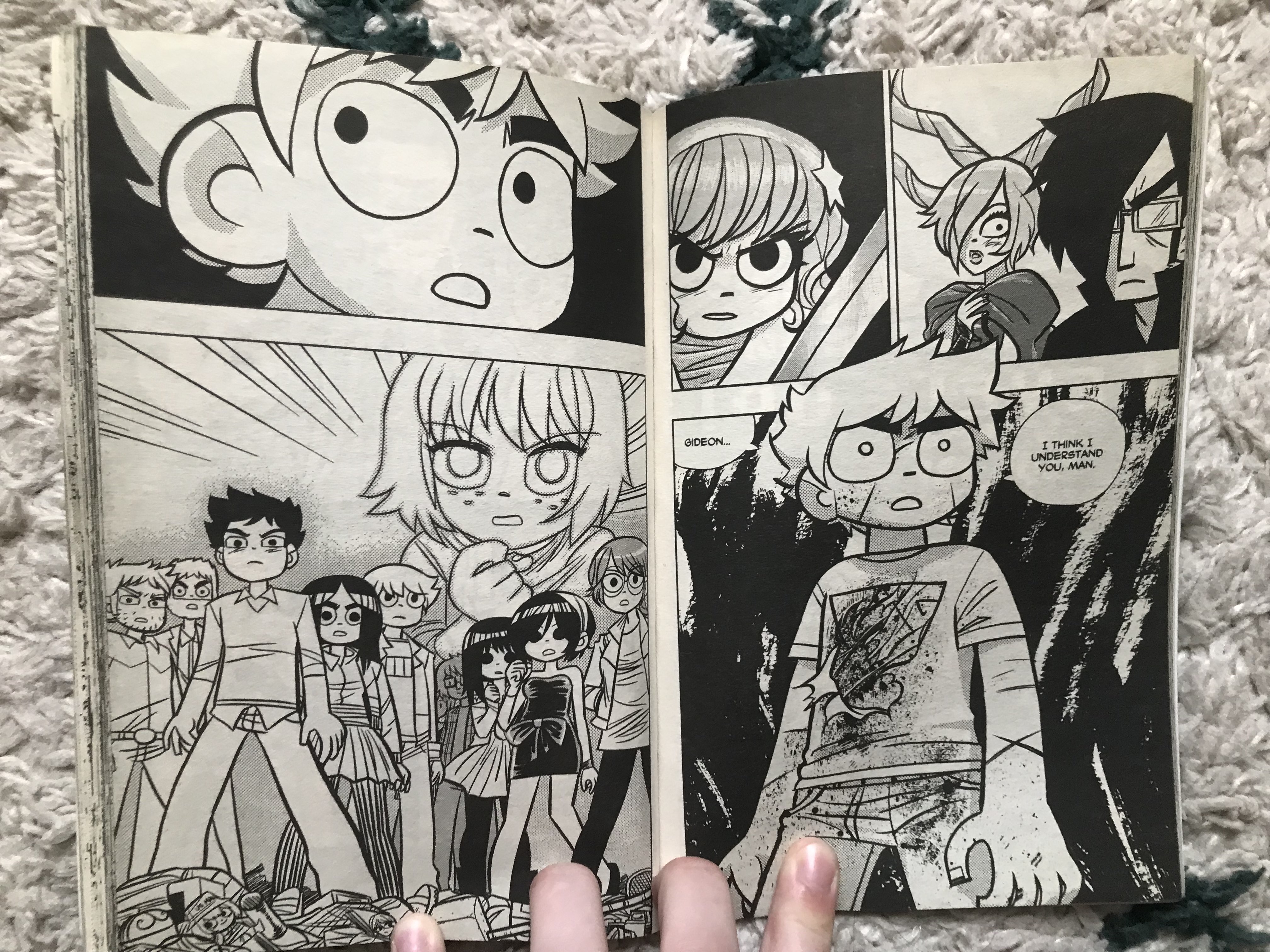

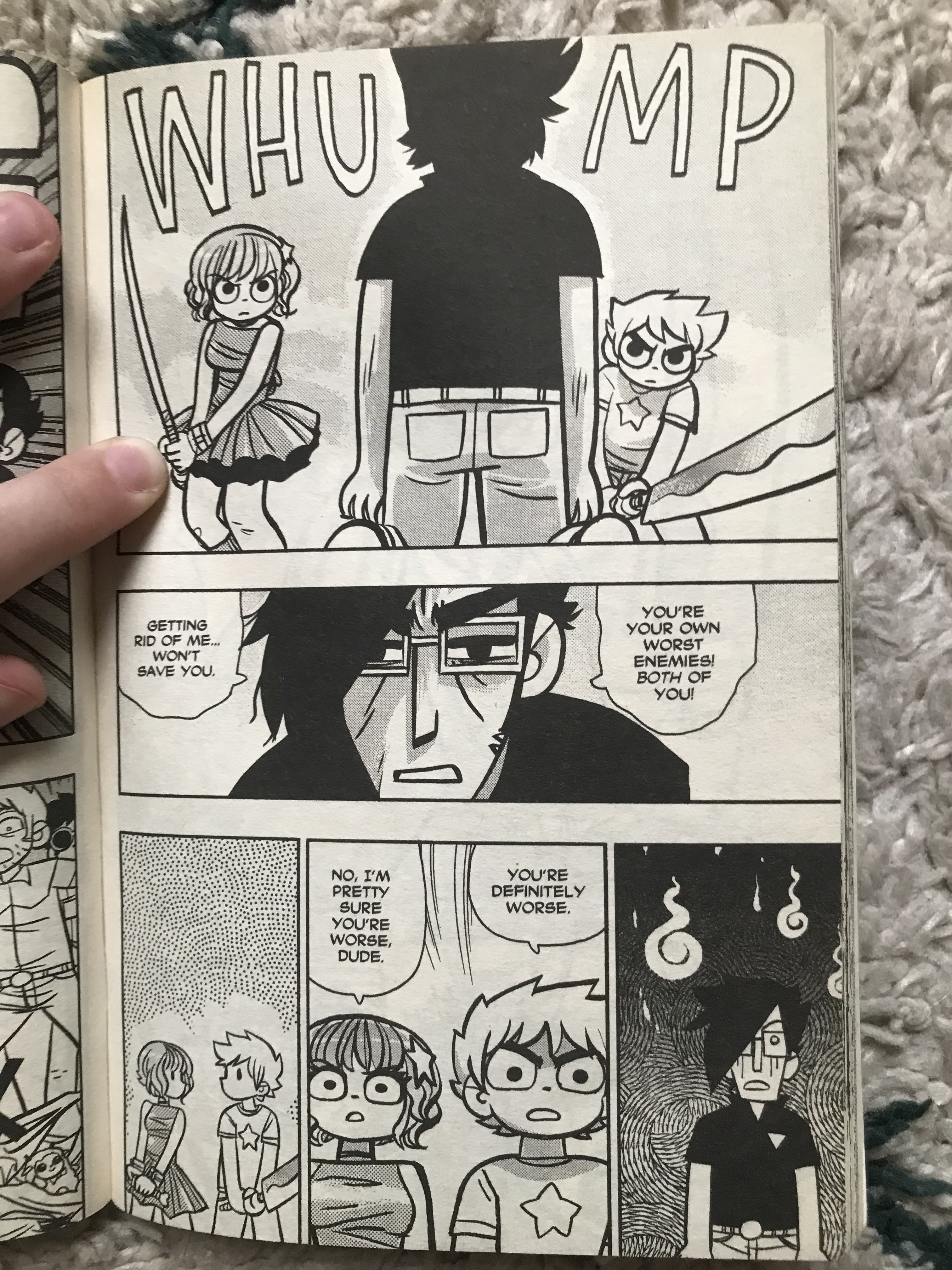

O’Malley’s years of studying film before comics show in the panelling choices he makes—establishing shots are common, and two panels that show the same shot on the same page are rare. This tight panelling means that when pages break from the form, whether that’s in spreads, leaving white space or giant panels, the content of those pages lands with impact. [examples—band spread in volume 1, gideon panel in book 3]

Towards the latter half of the series (books 4-6), O’Malley’s art style evolves into a more polished, anime-esque form. In keeping with the expressive janky quality of earlier volumes, he borrows the manga technique of using tiny, exaggerated drawings to convey big emotions, and starts using a bigger range of halftones more frequently, building up a more varied palette with only black ink. As the emotional crux of the story continues, there’s far more of those ‘break in the pattern’ pages, creating a slower and more thoughtful pace. This means, that when the story dwells on Scott and Ramona’s real pasts and the consequences of their actions, there’s plenty of time to consider it.

WORLD ONE, LEVEL TWO: IT’S STORYTIME

Saying that Scott Pilgrim is actually a really deep story instead of a silly one isn’t quite correct. The two elements don’t exist fully as opposites, they’re played off against each other to enhance both. If the expertly pulled off action scenes and jokes didn’t exist, the sudden turn the comic takes towards the end of Volume 4 wouldn’t feel as striking as it does. Characters seeming self-aware that they're in a comic (i.e. referencing previous volumes) sets up for how the comic will subvert the cliches it seems to be playing into.

Although I’m not as old as the characters in Scott Pilgrim, I still recognise something in their behaviour—this drive to feel like you’re ‘winning at life’, to put on a facade instead of addressing that you don’t know what you’re doing or that your friends suck. Almost everyone in Scott Pilgrim is exaggerating, trying to play the game of looking cool and hiding from consequences, vulnerability or criticism.

A quick plot summary: Scott is dating high-schooler Knives Chau mostly for bragging reasons, but when roller-skating subspace delivery girl Ramona Flowers starts travelling through his head, he becomes infatuated with her. After convincing Ramona to go out with him, dating them both for a short while, and defeating Ramona’s first evil ex-boyfriend (of seven) Matthew Patel, he breaks Knives’s heart and commits to Ramona. In Book 2 Scott defeats Lucas Lee, with much of the same light tone as the previous volume, but at the end, Scott’s ex, Envy Adams, reemerges back into his life. Volume 3 mostly covers trying to fight Todd Ingram, Ramona’s third evil ex, who is now dating Envy, and secretly cheating on her. Volume 3 still has some great fight scenes, but the emotional storytelling is ramped up as conflicts come to a head.

The latter half of the comic is where this theme emerges from its hiding place. Volume 4 introduces Roxie Richter, the only female evil ex (as much as I love the comic, it’s weird about lesbians,) and a non-evil non-ex of Scott’s, Lisa Miller, both of whom bring Scott and Ramona’s relationship into question. When both leads are enticed by the return of a person from their past, calling into question past relationships and susceptibilities to cheating, they have a falling-out.

NegaScott, Scott’s ‘evil’ counterpart, is first introduced near the end of Volume 4, but Scott doesn’t fight it yet—he ignores it.

Ultimately, Scott does get back with Ramona, and gains the power of Love, but with NegaScott, a physical manifestation of all Scott’s evil traits unconfronted, and Ramona’s mysterious past brushed aside, it isn’t a happy ending as much as the main characters think. The power of love doesn’t fix everything, because Scott Pilgrim isn’t operating on the cliche romcom level it’s set itself up to.

In Volume 5, the collapse continues. Ramona is struggling with feeling trapped and restless with Scott, and Scott is descending more into the realm of ‘pathetic and disliked by most of his friends.’ The friend group outside of him seems to be falling apart. Kyle and Ken Katayanagi, the double evil exes of Volume 5 (in a fight that follows the trend of Scott’s battles becoming more pathetic and losing their bombastic silly quality) dredge up more of Ramona’s complicated history with cheating and commitment. Scott begins to realise more of who Ramona actually is, beyond her enigmatic dream-girl cover. Because he’s Scott Pilgrim, Scott prevails, but comes home to find that Ramona has—left him.

When I first read this book at around 13, this really took me by surprise. It’s a really emotional scene, and the panelling choices help elevate it to that gut-punch level, but mainly I was surprised because, through the impressions of Scott Pilgrim I’d heard before and the themes the comic itself builds, rom-com love interests don’t usually leave their shitty partners, especially female ones, and they certainly don’t normally have actual negative character traits and impactful choices. I know ‘making your female characters have agency and flaws’ is a low bar, but I think it’s one that Scott Pilgrim plays with purposefully.

Although I mentioned how weird the comic is about gay women above, I do really like the way O’Malley writes women in Scott Pilgrim. I’m running into the ‘the bar is on the floor’ concept again, where it still surprises me when female characters are written with the basics of seeming like an actual human person, but I think the way characters interact with misogyny in Scott Pilgrim is also executed realistically. Kim’s place as Scott’s ‘back-up’ who he sees as always there for him passively until she decides not to be, Envy’s treatment like an accessory and how the people around her perceive her differently when she gets ‘hot’, even Knives’s eventual maturity all feel real.

Volume 6 is where all this character development comes to a head, as it’s revealed that Scott’s memories of times with his exes, and his fundamental perception of himself and his actions are flawed to non-existent. His dramatic backstory with saving Kim from high-school villains that opens Volume 2 turns out to have been just him beating up a random guy who liked her!

Defeating the evil exes isn’t the point, no matter how hard Scott fights, he has to reckon with the hardest thing of all—his own mistakes.

Because this is still a cliche romance story, Scott, understanding his past and the choices he has made, resolves to earn Ramona’s love back. And so he returns to Toronto, to fight Gideon Gordon Graves, Ramona’s final, most recent, and most evil ex.

WORLD TWO: I’VE SEEN FOOTAGE

Adaptation is a hard task, and I’m going to try not to come across too mean to Scott Pilgrim vs. The World, because a lot of the things I’m annoyed about it missing it had no chance to include, what with how incomplete the comic was at that time. The comics are dense, and due to the realities of making everything fit into film-length, a lot of background detail had to be cut. As a result of this, the movie has some elements of the comic’s finale, but the comic has an advantage of having more time to improve on the movie’s ending. The movie, thus, isn’t strictly an adaptation as much as it is an earlier script revision. I think that shows in how it handles what bits of Scott’s character arc it holds over, and what it’s included in the comics is a more compelling version of that arc.

WORLD TWO, LEVEL ONE: GIRLS ON FILM

Whether it’s for time reasons, development reasons or writing decisions made on the movie, Ramona is a far shallower character, and we never really see the side of her that in the comic she consciously hides. When Scott dies and comes back in the final battle and sees Ramona in subspace, it’s explained that instead of Ramona leaving of her own accord because of her own struggles, she’s been mind-controlled by Gideon to get back with him.

Although it’s technically consistent in both versions—the subspace highways are Gideon’s invention and used by him as a way to plant himself in Ramona’s mind as her innermost desire, in the same way Ramona accidentally got Scott obsessed with her—Ramona explicitly doesn’t go back to Gideon in the books. She ends up reduced from a character with her own agency and issues to an object who gets moved around by the men who date her.

While the comic addresses that some of Ramona’s early relationships weren’t necessarily out of love but out of convenience or expectation (Matthew Patel and Todd Ingram in particular, which follows the themes about ‘getting a life’ and following what you’re expected to do, and matches how Scott dates Knives for his own self-importance—however Ramona’s early relationships seem more dictated by experiencing misogyny than egotism,) this just feels like an early-draft, flatter version that what ends up making it into the comic. In the movie, this literal chip in her brain powers down when Scott kills Gideon, but in the comic, she herself throws him out of her head, ultimately making her the one in control of what she wants and able to move on and address her own issues.

Because the movie (despite still being a box office flop) had far more exposure than the comics, it defined the Scott Pilgrim characters in most peoples’ eyes as the versions, which lead to the conception of Ramona Flowers as the ‘manic pixie dream girl.’ ‘Manic Pixie Dream Girl’ as a term was coined before the movie release (but not the comics, it was 2007,) to describe a female character who exists only as a love interest, who is quirky and unusual and may be disliked for it but never unappealing and still distinctly girly, and has little to no character motives or interiority, just existing as a goal or companion for a man.

In the comics, Ramona’s characterisation as mysterious, unusual and desired is a built facade, but since the movie never goes beyond that she ends up as a blank character who helps Scott achieve happiness through the sole act of dating her. Similar things happen to Kim and Envy, the one-sided ways we see them through Scott’s eyes end up being taken as gospel in the movie and define their characters. Ramona’s reputation as a manic pixie dream girl then adds another layer onto the character and, in a strange recursive way, maybe even makes her eventual development more surprising.

WORLD TWO, LEVEL TWO: SUPERNOVA YOU ARE POWER

The movie’s battle with Gideon is largely in-keeping with the rest of it—Scott fights Gideon in a flashy battle scene for Ramona, Gideon steals the Power of Love, Knives appears to fight Ramona in another flashy action sequence, Gideon kills Scott. Scott uses his extra life from volume 5 to return and gains the Power of Self-Respect sword, apologises to Ramona and Knives for cheating on them, Scott and Knives team up, and Gideon is defeated.

I can see elements of what would become the second half of Volume 6, particularly Scott’s power of Self-Respect becoming the Power of Understanding in the comics—but without the extensive buildup showing Scott’s flaws and how hard they’ve impacted him, it doesn’t work as a redemption arc. Especially after he apologises for cheating and they both instantly forgive him, just because he promises to do better in future—without that reveal ahead, we don’t get the build-up needed to pull this off without it feeling like Scott’s just, once again, being an asshole who gets away with everything.

In the comic, after Gideon steals the power of love, after Scott dies and comes back, after Ramona comes back, dies, and comes back from that, the sword he gains is the Power of Understanding. Gideon, like Scott has been, is an entitled ‘I’m god’s gift to women’ proto-incel with the same kind of unawareness of the way he hurts women, represented by the Glow, a form of psychological warfare that traps people inside their own heads with no way to address their issues from an outside view. Although Gideon created the Glow, he ends up being an antidote to it for Scott, showing just exactly the kind of person he’s becoming. And when Scott enters inside Ramona’s head and sees the myth Gideon has constructed of himself, he asks, ‘Would you look at yourself?’

(note: The book states that Gideon is the one who twisted Scott’s memories, which I think detracts from the rest of what’s being said. The finale is all about Scott taking responsibility for his own actions, and this shifts responsibility onto Gideon.)

Look, let’s get this straight: Scott Pilgrim is definitely somewhat shitty boyfriend propaganda. For shitty boyfriends, and on behalf of shitty boyfriends. We don’t see the actual process of Scott changing for the better, just the first steps of confronting his flaws, and we certainly don’t see what being a better person looks like for him in the future—well, we don’t see their future at all. I think there’s plenty to criticise in narratives about men who can be fixed through a romantic relationship or aspiring to one, but I think it means a lot as a subversion of expectations that, in this somewhat big (for comics) comic that probably has the most appeal to guys who kind of are Scott Pilgrim, the final resolution of the story is that it’s not fighting or love that mends Scott and Ramona’s relationship, it’s both characters being able to come to terms with their issues and promise to improve.

WORLD THREE: WRAP IT UP AND START AGAIN

A while into my Scott Pilgrim reread, and while I was mentally planning this essay, the trailer for the Science Saru Scott Pilgrim Takes Off anime released. I’m tentatively excited: most of my issues with the movie stem from an unfinished plot and runtime cuts, so an anime that’s adapting from a finished piece might be the solution to a lot of the issues I have with Scott Pilgrim vs. the World.

Scott Pilgrim, in all existing incarnations (I have not played the video game, but I know of it,) straddles a weird line of being popular in niche circles, but never quite making it mainstream. The movie’s popularity has made its versions of the characters the most widely known, which then makes the latter half of the comic feel surprising and interesting—it’s already playing with your expectations from the genre, but having the movie exist as well heightens those expectations.

I don’t think the idea of having a romcom where the leading man has to change his ways is particularly subversive or unique, it kind of feels like the most basic thing to do when the genre is so saturated with shitty male protagonists and 2D love interests. The nature of mainstream popularity (at least, mainstream in the comic world) is that subversive concepts usually make it there last—I’m sure there are better twists on similar concepts somewhere out there.

Despite that, it still upsets me that we never got to see the latter half of the comic’s emotional storytelling realised in movie form. I probably would still hold to the opinion that the comics are better, but the message Scott Pilgrim ends on does feel exciting for a lauded movie, especially one that’s since become lauded by film-bros who resemble Scott in more ways than they’d like to hear. I shouldn’t depend on media for my activism, it doesn’t get anything done. Even if the movie ended the same way the comic does, it wouldn’t have much large-scale impact on the way those guys act, but it still feels… important, and sad, to see a genuinely interesting piece of art get seen by most people as what feels like a shallow form of itself.

Thanks for reading! I realise this kind of follows a lot of the same beats as two months ago’s Discworld essay, in that it’s largely about playing with your expectations about a piece of media. Still, I enjoyed writing it, and especially enjoyed revisiting a piece of media that I really enjoy. Also, it’s my birthday tomorrow! Hope the constant photos didn't get too annoying, I just honestly love the way the comic looks. Well, next blog post will be at the end of August/beginning of September—there may be a delay because I’m starting university. seeya then! :)

Unfortunately, what had to go, and ended up disappearing from most people’s idea of what Scott Pilgrim was, were the most interesting aspects of the comic (at least to me.) Because Scott Pilgrim isn’t really a story about cool fights and dream girls—well, it is, but Scott Pilgrim is a story of how cool fights and dream girls are both facades for these painfully human, complex dynamics and pasts, and beneath its bombastic action lies an unexpected and fascinating story that the movie misses, and ends up presenting a shallower and more misogynistic piece of art.

Furthermore, that ‘cult classic’ status, and the way the comic plays with expectations and metanarrative, has caused it to develop a sort of aura of reputation and tropes that makes reading and watching it this fascinating thematic soup—and baby, I have autism, so let’s get picking bits out of it.

WORLD ONE: TIME-TRAVELLING DIAMOND-CUTTER SHAPED HEARTACHE

WORLD ONE, LEVEL ONE: MAKE IT OR BREAK IT

A key part of experiencing the Scott Pilgrim comics is how they evolve over time. A comic’s job is to seamlessly match up art to writing to panelling, and over the course of the 6 volumes, all three grow in complexity. Scott Pilgrim’s early messy and simplistic art style (grounded by a solid understanding of 3D form) feels perfectly in step with its off-beat, awkward dialogue. At this point in the comics, Scott is an affable asshole mocked by all of his friends, who seems to get everything he wants—’If your life had a face, I’d punch it.’

This speed is largely upheld by the panelling. Panelling, similar to video editing, is an invisible art that holds everything together. Unless you’re a nerd, like me, you’re probably not taking active notice of how a comic is panelled when you read it, but it’s integral to how you experience it, because it frames (literally) the comic in time. The panelling in the first half of Scott Pilgrim is effortlessly pacy, and sticks to a strong structure: full bleed panels every page, taking up as much page space as possible, giving us speed and efficiency in what it shows. The ridiculous fights, crazy concepts like subspace, and Scott’s own awful behaviour are all held in place and made easy to accept by the fact the comic never stops and gives you enough time to actually think about what’s happening.

O’Malley’s years of studying film before comics show in the panelling choices he makes—establishing shots are common, and two panels that show the same shot on the same page are rare. This tight panelling means that when pages break from the form, whether that’s in spreads, leaving white space or giant panels, the content of those pages lands with impact. [examples—band spread in volume 1, gideon panel in book 3]

Towards the latter half of the series (books 4-6), O’Malley’s art style evolves into a more polished, anime-esque form. In keeping with the expressive janky quality of earlier volumes, he borrows the manga technique of using tiny, exaggerated drawings to convey big emotions, and starts using a bigger range of halftones more frequently, building up a more varied palette with only black ink. As the emotional crux of the story continues, there’s far more of those ‘break in the pattern’ pages, creating a slower and more thoughtful pace. This means, that when the story dwells on Scott and Ramona’s real pasts and the consequences of their actions, there’s plenty of time to consider it.

WORLD ONE, LEVEL TWO: IT’S STORYTIME

Saying that Scott Pilgrim is actually a really deep story instead of a silly one isn’t quite correct. The two elements don’t exist fully as opposites, they’re played off against each other to enhance both. If the expertly pulled off action scenes and jokes didn’t exist, the sudden turn the comic takes towards the end of Volume 4 wouldn’t feel as striking as it does. Characters seeming self-aware that they're in a comic (i.e. referencing previous volumes) sets up for how the comic will subvert the cliches it seems to be playing into.

Although I’m not as old as the characters in Scott Pilgrim, I still recognise something in their behaviour—this drive to feel like you’re ‘winning at life’, to put on a facade instead of addressing that you don’t know what you’re doing or that your friends suck. Almost everyone in Scott Pilgrim is exaggerating, trying to play the game of looking cool and hiding from consequences, vulnerability or criticism.

A quick plot summary: Scott is dating high-schooler Knives Chau mostly for bragging reasons, but when roller-skating subspace delivery girl Ramona Flowers starts travelling through his head, he becomes infatuated with her. After convincing Ramona to go out with him, dating them both for a short while, and defeating Ramona’s first evil ex-boyfriend (of seven) Matthew Patel, he breaks Knives’s heart and commits to Ramona. In Book 2 Scott defeats Lucas Lee, with much of the same light tone as the previous volume, but at the end, Scott’s ex, Envy Adams, reemerges back into his life. Volume 3 mostly covers trying to fight Todd Ingram, Ramona’s third evil ex, who is now dating Envy, and secretly cheating on her. Volume 3 still has some great fight scenes, but the emotional storytelling is ramped up as conflicts come to a head.

The latter half of the comic is where this theme emerges from its hiding place. Volume 4 introduces Roxie Richter, the only female evil ex (as much as I love the comic, it’s weird about lesbians,) and a non-evil non-ex of Scott’s, Lisa Miller, both of whom bring Scott and Ramona’s relationship into question. When both leads are enticed by the return of a person from their past, calling into question past relationships and susceptibilities to cheating, they have a falling-out.

NegaScott, Scott’s ‘evil’ counterpart, is first introduced near the end of Volume 4, but Scott doesn’t fight it yet—he ignores it.

Ultimately, Scott does get back with Ramona, and gains the power of Love, but with NegaScott, a physical manifestation of all Scott’s evil traits unconfronted, and Ramona’s mysterious past brushed aside, it isn’t a happy ending as much as the main characters think. The power of love doesn’t fix everything, because Scott Pilgrim isn’t operating on the cliche romcom level it’s set itself up to.

In Volume 5, the collapse continues. Ramona is struggling with feeling trapped and restless with Scott, and Scott is descending more into the realm of ‘pathetic and disliked by most of his friends.’ The friend group outside of him seems to be falling apart. Kyle and Ken Katayanagi, the double evil exes of Volume 5 (in a fight that follows the trend of Scott’s battles becoming more pathetic and losing their bombastic silly quality) dredge up more of Ramona’s complicated history with cheating and commitment. Scott begins to realise more of who Ramona actually is, beyond her enigmatic dream-girl cover. Because he’s Scott Pilgrim, Scott prevails, but comes home to find that Ramona has—left him.

When I first read this book at around 13, this really took me by surprise. It’s a really emotional scene, and the panelling choices help elevate it to that gut-punch level, but mainly I was surprised because, through the impressions of Scott Pilgrim I’d heard before and the themes the comic itself builds, rom-com love interests don’t usually leave their shitty partners, especially female ones, and they certainly don’t normally have actual negative character traits and impactful choices. I know ‘making your female characters have agency and flaws’ is a low bar, but I think it’s one that Scott Pilgrim plays with purposefully.

Although I mentioned how weird the comic is about gay women above, I do really like the way O’Malley writes women in Scott Pilgrim. I’m running into the ‘the bar is on the floor’ concept again, where it still surprises me when female characters are written with the basics of seeming like an actual human person, but I think the way characters interact with misogyny in Scott Pilgrim is also executed realistically. Kim’s place as Scott’s ‘back-up’ who he sees as always there for him passively until she decides not to be, Envy’s treatment like an accessory and how the people around her perceive her differently when she gets ‘hot’, even Knives’s eventual maturity all feel real.

Volume 6 is where all this character development comes to a head, as it’s revealed that Scott’s memories of times with his exes, and his fundamental perception of himself and his actions are flawed to non-existent. His dramatic backstory with saving Kim from high-school villains that opens Volume 2 turns out to have been just him beating up a random guy who liked her!

Defeating the evil exes isn’t the point, no matter how hard Scott fights, he has to reckon with the hardest thing of all—his own mistakes.

Because this is still a cliche romance story, Scott, understanding his past and the choices he has made, resolves to earn Ramona’s love back. And so he returns to Toronto, to fight Gideon Gordon Graves, Ramona’s final, most recent, and most evil ex.

WORLD TWO: I’VE SEEN FOOTAGE

Adaptation is a hard task, and I’m going to try not to come across too mean to Scott Pilgrim vs. The World, because a lot of the things I’m annoyed about it missing it had no chance to include, what with how incomplete the comic was at that time. The comics are dense, and due to the realities of making everything fit into film-length, a lot of background detail had to be cut. As a result of this, the movie has some elements of the comic’s finale, but the comic has an advantage of having more time to improve on the movie’s ending. The movie, thus, isn’t strictly an adaptation as much as it is an earlier script revision. I think that shows in how it handles what bits of Scott’s character arc it holds over, and what it’s included in the comics is a more compelling version of that arc.

WORLD TWO, LEVEL ONE: GIRLS ON FILM

Whether it’s for time reasons, development reasons or writing decisions made on the movie, Ramona is a far shallower character, and we never really see the side of her that in the comic she consciously hides. When Scott dies and comes back in the final battle and sees Ramona in subspace, it’s explained that instead of Ramona leaving of her own accord because of her own struggles, she’s been mind-controlled by Gideon to get back with him.

Although it’s technically consistent in both versions—the subspace highways are Gideon’s invention and used by him as a way to plant himself in Ramona’s mind as her innermost desire, in the same way Ramona accidentally got Scott obsessed with her—Ramona explicitly doesn’t go back to Gideon in the books. She ends up reduced from a character with her own agency and issues to an object who gets moved around by the men who date her.

While the comic addresses that some of Ramona’s early relationships weren’t necessarily out of love but out of convenience or expectation (Matthew Patel and Todd Ingram in particular, which follows the themes about ‘getting a life’ and following what you’re expected to do, and matches how Scott dates Knives for his own self-importance—however Ramona’s early relationships seem more dictated by experiencing misogyny than egotism,) this just feels like an early-draft, flatter version that what ends up making it into the comic. In the movie, this literal chip in her brain powers down when Scott kills Gideon, but in the comic, she herself throws him out of her head, ultimately making her the one in control of what she wants and able to move on and address her own issues.

Because the movie (despite still being a box office flop) had far more exposure than the comics, it defined the Scott Pilgrim characters in most peoples’ eyes as the versions, which lead to the conception of Ramona Flowers as the ‘manic pixie dream girl.’ ‘Manic Pixie Dream Girl’ as a term was coined before the movie release (but not the comics, it was 2007,) to describe a female character who exists only as a love interest, who is quirky and unusual and may be disliked for it but never unappealing and still distinctly girly, and has little to no character motives or interiority, just existing as a goal or companion for a man.

In the comics, Ramona’s characterisation as mysterious, unusual and desired is a built facade, but since the movie never goes beyond that she ends up as a blank character who helps Scott achieve happiness through the sole act of dating her. Similar things happen to Kim and Envy, the one-sided ways we see them through Scott’s eyes end up being taken as gospel in the movie and define their characters. Ramona’s reputation as a manic pixie dream girl then adds another layer onto the character and, in a strange recursive way, maybe even makes her eventual development more surprising.

WORLD TWO, LEVEL TWO: SUPERNOVA YOU ARE POWER

The movie’s battle with Gideon is largely in-keeping with the rest of it—Scott fights Gideon in a flashy battle scene for Ramona, Gideon steals the Power of Love, Knives appears to fight Ramona in another flashy action sequence, Gideon kills Scott. Scott uses his extra life from volume 5 to return and gains the Power of Self-Respect sword, apologises to Ramona and Knives for cheating on them, Scott and Knives team up, and Gideon is defeated.

I can see elements of what would become the second half of Volume 6, particularly Scott’s power of Self-Respect becoming the Power of Understanding in the comics—but without the extensive buildup showing Scott’s flaws and how hard they’ve impacted him, it doesn’t work as a redemption arc. Especially after he apologises for cheating and they both instantly forgive him, just because he promises to do better in future—without that reveal ahead, we don’t get the build-up needed to pull this off without it feeling like Scott’s just, once again, being an asshole who gets away with everything.

In the comic, after Gideon steals the power of love, after Scott dies and comes back, after Ramona comes back, dies, and comes back from that, the sword he gains is the Power of Understanding. Gideon, like Scott has been, is an entitled ‘I’m god’s gift to women’ proto-incel with the same kind of unawareness of the way he hurts women, represented by the Glow, a form of psychological warfare that traps people inside their own heads with no way to address their issues from an outside view. Although Gideon created the Glow, he ends up being an antidote to it for Scott, showing just exactly the kind of person he’s becoming. And when Scott enters inside Ramona’s head and sees the myth Gideon has constructed of himself, he asks, ‘Would you look at yourself?’

(note: The book states that Gideon is the one who twisted Scott’s memories, which I think detracts from the rest of what’s being said. The finale is all about Scott taking responsibility for his own actions, and this shifts responsibility onto Gideon.)

Look, let’s get this straight: Scott Pilgrim is definitely somewhat shitty boyfriend propaganda. For shitty boyfriends, and on behalf of shitty boyfriends. We don’t see the actual process of Scott changing for the better, just the first steps of confronting his flaws, and we certainly don’t see what being a better person looks like for him in the future—well, we don’t see their future at all. I think there’s plenty to criticise in narratives about men who can be fixed through a romantic relationship or aspiring to one, but I think it means a lot as a subversion of expectations that, in this somewhat big (for comics) comic that probably has the most appeal to guys who kind of are Scott Pilgrim, the final resolution of the story is that it’s not fighting or love that mends Scott and Ramona’s relationship, it’s both characters being able to come to terms with their issues and promise to improve.

WORLD THREE: WRAP IT UP AND START AGAIN

A while into my Scott Pilgrim reread, and while I was mentally planning this essay, the trailer for the Science Saru Scott Pilgrim Takes Off anime released. I’m tentatively excited: most of my issues with the movie stem from an unfinished plot and runtime cuts, so an anime that’s adapting from a finished piece might be the solution to a lot of the issues I have with Scott Pilgrim vs. the World.

Scott Pilgrim, in all existing incarnations (I have not played the video game, but I know of it,) straddles a weird line of being popular in niche circles, but never quite making it mainstream. The movie’s popularity has made its versions of the characters the most widely known, which then makes the latter half of the comic feel surprising and interesting—it’s already playing with your expectations from the genre, but having the movie exist as well heightens those expectations.

I don’t think the idea of having a romcom where the leading man has to change his ways is particularly subversive or unique, it kind of feels like the most basic thing to do when the genre is so saturated with shitty male protagonists and 2D love interests. The nature of mainstream popularity (at least, mainstream in the comic world) is that subversive concepts usually make it there last—I’m sure there are better twists on similar concepts somewhere out there.

Despite that, it still upsets me that we never got to see the latter half of the comic’s emotional storytelling realised in movie form. I probably would still hold to the opinion that the comics are better, but the message Scott Pilgrim ends on does feel exciting for a lauded movie, especially one that’s since become lauded by film-bros who resemble Scott in more ways than they’d like to hear. I shouldn’t depend on media for my activism, it doesn’t get anything done. Even if the movie ended the same way the comic does, it wouldn’t have much large-scale impact on the way those guys act, but it still feels… important, and sad, to see a genuinely interesting piece of art get seen by most people as what feels like a shallow form of itself.

Thanks for reading! I realise this kind of follows a lot of the same beats as two months ago’s Discworld essay, in that it’s largely about playing with your expectations about a piece of media. Still, I enjoyed writing it, and especially enjoyed revisiting a piece of media that I really enjoy. Also, it’s my birthday tomorrow! Hope the constant photos didn't get too annoying, I just honestly love the way the comic looks. Well, next blog post will be at the end of August/beginning of September—there may be a delay because I’m starting university. seeya then! :)